Short story of the Gaza strip

Gaza: “land of crossings, land of paths.” Ancient Gaza, once flourishing: today a land to be saved.

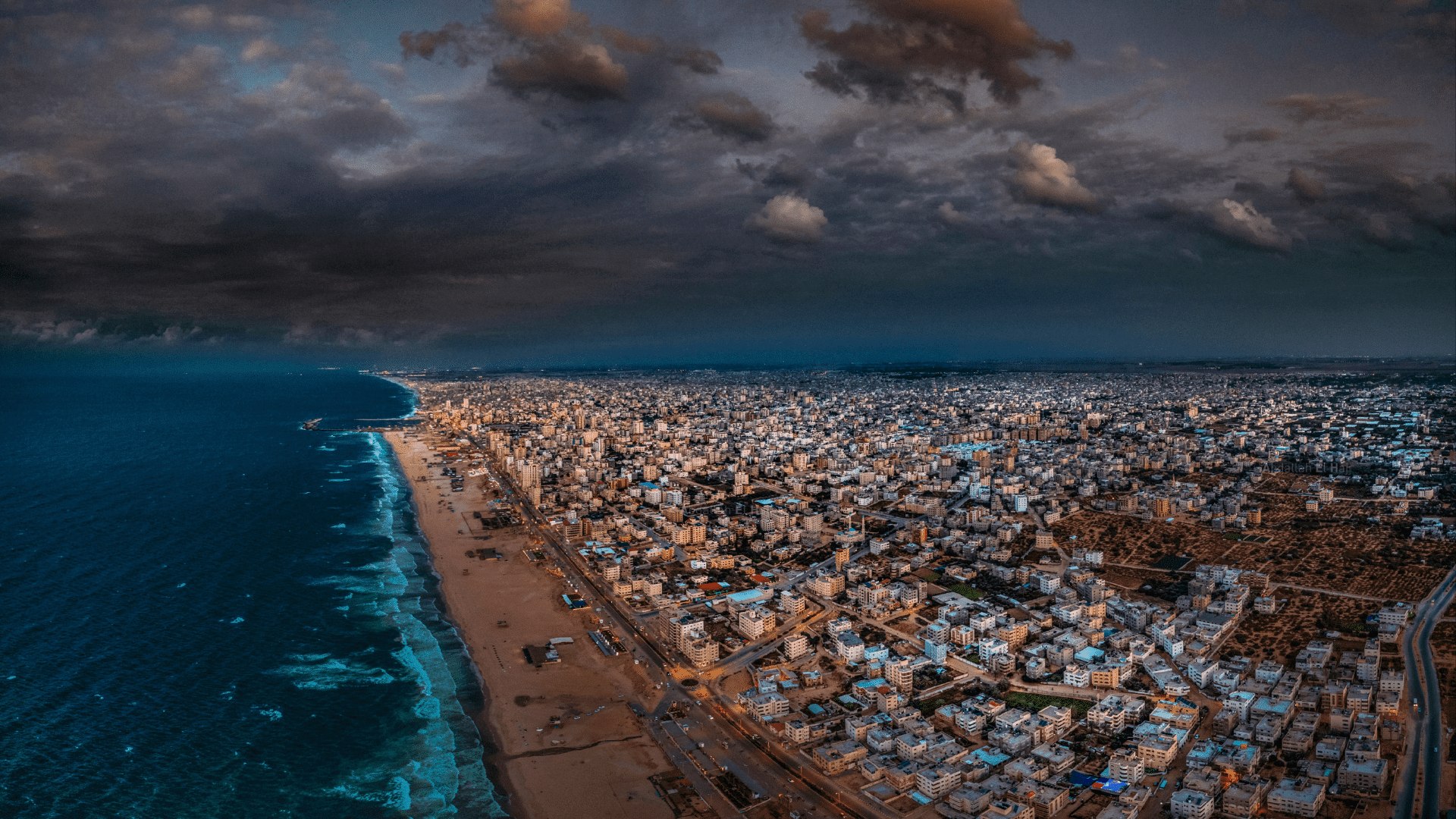

The “Gaza Strip” owes its name to the size and shape of the territory indicated by this toponym: a strip, a thin piece of land jutting into the Mediterranean Sea. Just over 360 km² of land, beach, and sky, fertile fields where a thriving agriculture once developed: 360 km² that today are the stage of one of the most terrible and painful scenarios in modern history.

But where exactly is Gaza located? What events, what decisions have led to the tragedy we see today? The history, geography, and traditions of Gaza—older and more enduring than we usually think—help us reconstruct the identity of a place and a people that, today, it is increasingly urgent to look at, narrate, and listen to.

Where is Gaza?

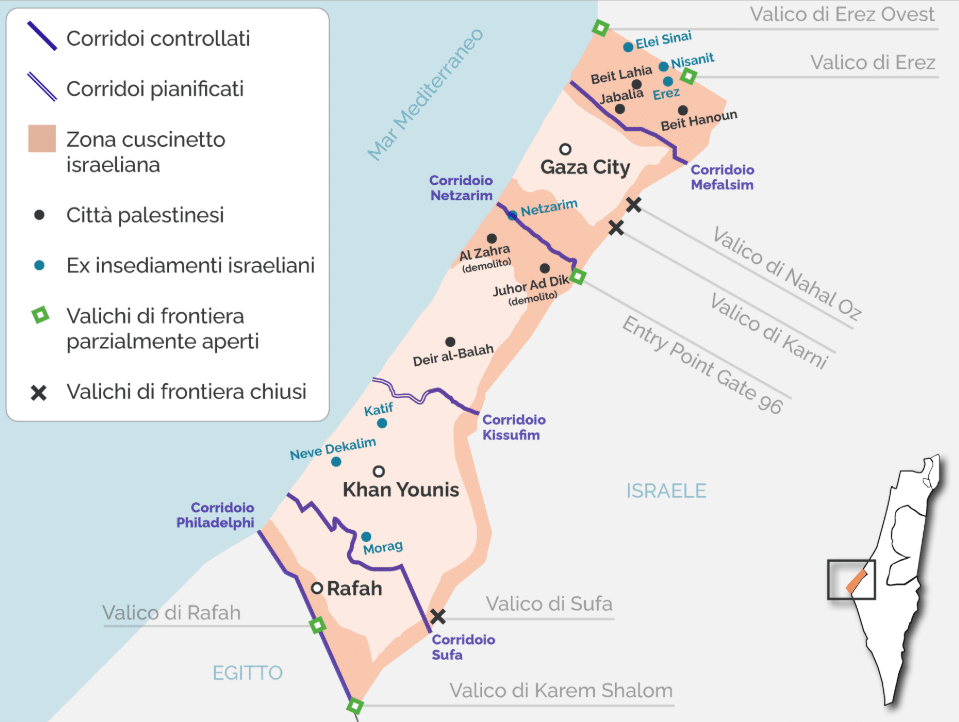

The Gaza Strip is an exclave of the Palestinian Territories, which extend mostly a little further north-west in the area known as the “West Bank.” To the north-east lies the State of Israel, to the south Egypt—accessible through the Rafah crossing; to the west, only the vast blue of the Mediterranean Sea.

Moving from north to south, one finds Gaza City, the capital and most populated urban center, Khan Younis, and Rafah: the three main cities of the Strip, once flourishing hubs of cultural and commercial exchange, today irreparably damaged with tens of thousands of destroyed buildings in each, and a population killed, wounded, or displaced. Other towns in the Strip—north to south: Beit Lahiya, Jabalia, Beit Hanoun, Deir al-Balah, Bani Suheila, Abu Middein, Al-Mawasi—have largely become reception centers or refugee camps for those fleeing the hardest-hit or attacked areas. In Deir al-Balah, for example, there is now a large refugee camp where Pro Terra Sancta, together with local partner Atfaluna Society, organizes humanitarian aid and psychological support activities for families and children affected by the war.

History today: occupation, Israel, Hamas, the war in Gaza

Within the complex and tragic war between Israel and Palestine (for further insights: part 1 and part 2), Gaza has unfortunately become one of the focal points of the conflict.

From 1917, with the Balfour Declaration, began the international contention—whose main actors were the British, the Arabs of Egypt, and Zionist Jews migrating to the land of Israel—over the territories of Palestine (the so-called Palestinian question). Through the Arab-Israeli wars, the Nakba, the Yom Kippur War, and the Intifadas, Gaza and all of Palestine were brought to the destruction of which we are witnesses today.

Hamas

The pressures of revolt and Israel’s harsh repression of the First Intifada, in 1987, created the fertile ground in which Hamas was born: a radical movement whose name, in Arabic, is the acronym for the Islamic Resistance Movement (Ḥarakat al-Muqāwama al-Islāmiyya). At once a political party and an armed branch that has used terrorist actions as a weapon of combat, Hamas is a religious and militant group with deep Islamist roots, born as an armed resistance movement against the State of Israel and at the same time a promoter of social and religious activities, especially in Gaza.

Compared to the PLO—the Palestine Liberation Organization, the other major Palestinian political party, founded in 1964—Hamas’ approach is far more radical: always against any attempt at reconciliation or compromise, it rejects the two-state solution supported by the PLO in 1988, and considers armed struggle the only possible path to the liberation of Palestine. In 2006 Hamas won the Palestinian elections and took political control of the region, causing great fear and upheaval internationally.

The pressures of the Western world and the irreconcilable positions of Hamas and the PLO led to both a political and territorial split of Palestine: the PLO, together with the PA (Palestinian Authority, an autonomous government born from the Oslo Accords with the function of territorial administration), kept control of the West Bank, while Hamas, in 2007, seized control of the Gaza Strip, establishing military rule.

Israel’s military operations

Israel’s attempts to occupy Palestinian territories and the attacks of Palestinian armed groups such as Al-Qassam and Hamas unfold throughout the conflict, increasingly involving Gaza’s land and population.

Israel established settlements in the Strip with the declared aim of protecting its borders and dismantling Hamas’ terrorist networks. In 2005, the so-called Israeli Unilateral Disengagement Plan, promoted by the Israeli Prime Minister, removed settlements from the Strip and some from the northern West Bank; however, this operation failed to end clashes between Israel and Palestinian armed groups, which continued and intensified after Hamas’ electoral victory.

Operation Cast Lead in December 2008 was the first of numerous Israeli attacks on Gaza, aimed at dismantling Hamas. The military campaign, through heavy bombings and ground attacks, caused in twenty-two days the deaths of about 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. One of the most debated targets of the attack was the al-Fakhura school, in the north of the Strip, used as a shelter for displaced civilians by the UN: according to Israel, it was a Hamas outpost from which rockets had been launched.

Many other Israeli military campaigns followed, officially targeting Hamas bases but continuing to cause thousands of civilian casualties. In 2017 Hamas, for the first time, accepted the 1967 borders as those of the Palestinian state, thus formally accepting a territorial division with Israel—although it still does not officially recognize the State of Israel.

The latest Israeli offensive, launched in response to Hamas’ attack of October 7, 2023 and prolonged until today, has caused irreparable damage: as of September 2025, Palestinian victims are estimated at around 65,000 and more than 160,000 injured; Gaza City and Rafah are almost completely destroyed, over half a million displaced, and living conditions keep deteriorating.

Humanitarian aid deliveries have been repeatedly blocked or interrupted, leading to a famine declared by the United Nations on August 22, 2025: more than 500,000 people are in severe food insecurity, and more than 130,000 children are at risk of death due to malnutrition. This situation has sparked protest movements across the international scene; in the summer of 2025, an international civilian-led humanitarian initiative set out to break the Israeli blockade on aid to Gaza: the Global Sumud Flotilla. The name refers to a civilian fleet (flotilla: a small fleet organized by civil society and not militarily), global (with boats from over 44 countries), promoting steadfast resistance in the face of difficulties encountered during navigation (ṣumūd in Arabic means resistance, resilience, perseverance in the face of obstacles). As of today, the ships are on their way to Gaza, attempting to reach the population and deliver the aid they carry.

Pro Terra Sancta relies on the Latin Parish of Gaza City and local partners to provide first aid support: food, blankets, and essential goods. Our emergency aid campaign in Gaza and Palestine has long been active, adapting to urgent needs while always keeping attention on the psychological damage caused by today’s living conditions in Gaza.

History Yesterday: 3,500 years ago

The toponym “Gaza” is ancient, very ancient: a Byzantine mosaic, located at Umm ar-Rasas and dating back to 758 AD, depicts the main Middle Eastern cities of the time—and among them appears Gaza.

Gaza has borne the same name for at least 3,500 years; as journalist Paola Caridi said in a lectio magistralis at the University for Foreigners of Siena on January 22, 2025:

“Like trees, cities set down their roots. And when they are displaced—even by human beings—they lose their landmarks, their cardinal points, their perspectives. Gaza has always been there, and it is the permanence of the name itself that confirms it.”

Reducing Gaza to the ghost of a destroyed city, to nothing more than a land of war, an unhappy land doomed by fate, means erasing all the history that predates the “short century.” Gaza was once a flourishing land, rich in trade, merchants, colors along its streets; to use Caridi’s words again, it was a “land of crossings, land of paths”; “a land already in bloom, not a desert to be made bloom.”

Let us briefly review its history.

The Gaza Strip from its origins to the Hellenistic period

The city of Gaza has a millenary history dating back to the Early Bronze Age (3500–3000 BC). Located along the coast of Palestine, it occupied a strategic position on the Via Maris, an ancient trade route linking Egypt to Syria and Mesopotamia, serving as a crossroads between three continents.

The earliest settlement in the region, Tell Al-Sakan, five kilometers south of present-day Gaza, was originally an Egyptian fortress. Gaza’s port, under agreements with Egypt, was an important hub of commercial exchange, particularly for timber imported from Lebanon.

After Tell Al-Sakan was abandoned, a new urban center began to develop further inland around 2000 BC, called Tell Al-Ajjul. However, this settlement ceased to exist in the 14th century BC with the emergence of the city of Gaza, which rose on the same site as the modern city. Gaza became the Egyptian administrative capital of the region.

Around 1200 BC, the Philistines, a people of uncertain origin who settled along the Mediterranean coast and from whom Palestine (“land of the Philistines”) takes its name, occupied Gaza. It is precisely in this period that the Book of Judges places the story of the Israelite judge Samson, known for his superhuman strength. Betrayed by Delilah, a Philistine woman he loved, Samson lost the power contained in his long hair. Captured by the Philistines, his eyes were gouged out and he was imprisoned. During a feast in the temple of the Philistine god Dagon, Samson prayed to God to restore his strength. God granted his request, and while bound to the temple pillars, Samson brought the temple down upon the Philistines, dying with them.

During the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods (9th century BC – 539 BC), the city, used as a gateway between Egypt and Syria, continued to be contested. Later allied with Cyrus the Great of Persia, Gaza experienced significant development in this period.

Remembered by Herodotus, Gaza continued to play a key role as a commercial crossroads for caravan routes. Alexander the Great conquered it in 332 BC, and after his death one of the decisive battles among his successors was fought there. At that time, Gaza was pagan and strongly influenced by Hellenistic culture.

The Roman era and the spread of Christianity

After being besieged and destroyed by the Maccabees and the Hasmoneans, the city was conquered and gradually rebuilt by the Romans in 64–63 BC, following the model of other Eastern Roman cities. In the 2nd century AD, it became a prosperous city thanks to the incense trade and viticulture.

Through the efforts of Bishop Porphyry (347–420 AD), who led the small Christian community for 25 years, Christianity spread in Gaza, though not without difficulty. Clashes with pagans were frequent, and Porphyry appealed to Empress Eudocia, mother of the future Theodosius II, who ordered the destruction of pagan temples, followed by the construction of the first churches. The body of Saint Porphyry is preserved in the Greek Orthodox church dedicated to him, bombed in October 2023.

Gaza also became an important port for Christian pilgrims heading toward Sinai. Testimonies of this Byzantine period survive through beautiful floor mosaics that decorated the churches of the time. These mosaics are tangible signs of the importance and prosperity Gaza knew during the Christian era.

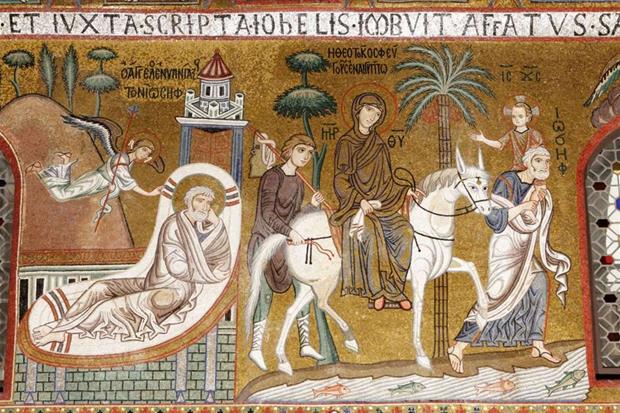

Finally, Christian tradition connects Gaza to an important chapter in Christian history. According to some apocryphal gospels, such as the Protoevangelium of James and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Holy Family passed through Gaza during the Flight into Egypt.

The advent of Islam and Ottoman rule in Gaza

In 634 AD, Gaza was conquered by the Arabs and—apart from about eighty years under the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem after the Crusades—remained under Islamic rule until the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1917.

Fatimids, Mongols, and Mamluks alternated control until the Ottoman conquest in 1517. During the Turco-Mamluk war (1516–1517), Gaza became part of the Sanjak of Gaza. It then suffered economic decline due to poor governance. Later, it was administered by governors sent from Constantinople

From the British Mandate to the birth of the State of Israel

At the end of World War I, with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, Gaza and all of Palestine came under British administration, under a League of Nations mandate. This period, lasting until 1948, saw growing tensions between the Jewish and Arab populations, as well as increasing Jewish immigration.

World War II further deepened these divisions: Jews contributed to the Allied war effort, while Arabs viewed the war as an opportunity to reaffirm their identity and renew their struggle against the Jewish presence in Palestine.

With the end of the war, in 1947, the famous UN Resolution 181 was passed. It recommended the partition of Palestine into two independent states: one Jewish (56% of the territory) and one Arab (34% of the territory), with Jerusalem under international control. Despite Palestinian opposition, Resolution 181 was ratified. On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Zionist movement, proclaimed the independence of the State of Israel after the withdrawal of British troops.

A culture to preserve: “remember Gaza in order to tell its story”

In the already mentioned Umm al-Rasas mosaic, Gaza is represented by its public buildings, bearing witness to a city rich in art, history, and culture. The mosaic, discovered and restored by archaeologist Father Michele Piccirillo, stands as a speaking testimony of an ancient and glorious history, an affirmation of a cultural and artistic identity that cannot disappear under the smoke of missiles and the rubble.

“Remember Gaza in order to tell its story,” says Paola Caridi: to remember in order to tell everything—not just a part—and to keep alive the history of a people and of the individuals who, even today, bear witness to and claim its existence.